Notes of H3A

Notes of H3A

English Reading Group Meeting

Wednesday 5th December 2012

The Innocents Abroad By Mark Twain

…and never the Twain shall meet.1

(It) is not a work of humor but of ridicule.2

In the first quotation, Rudyard Kipling was talking about East and West, but he could have been talking about our reading group at the end of our discussion of Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad. The second quote could have come straight from our group. It is probably no exaggeration to say that this book polarised the group more than any other book we have read so far.

What was striking about our discussion was how our views on Twain seemed to be so much at odds with the popular view of him as the father of the Great American Novel.

For example, to William Faulkner, Twain was

the first truly American writer, and all of us since are his heirs.

To Ernest Hemingway:

All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called “Huckleberry Finn” – all American writing comes from that. There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.

Norman Mailer thought

The mark of how good ‘”Huckleberry Finn” has to be is that one can compare it to a number of our best modern American novels and it stands up page for page, awkward here, sensational there – absolutely the equal of one of those rare incredible first novels that come along once or twice in a decade.

HL Mencken said

I believe that Mark Twain had a clearer vision of life, that he came nearer to its elementals and was less deceived by its false appearances, than any other American who has ever presumed to manufacture generalizations, not excepting Emerson. I believe that he was the true father of our national literature, the first genuinely American artist of the royal blood.3

Within our group, one American member said of Twain that he thinks of him

as a kind of mentor, a very interesting character, a fabulous writer. “Huckleberry Finn” is as close as it gets to the Great American Novel.

However, speaking of The Innocents Abroad, the same member recalled

I had read this before, but when I went back to it I was really offended.

A sample of comments from other members gives an indication of the level of polarisation within the group:

He’s racist, especially against Turks; it really gets my blood boiling.

He’s bigoted, biased, not an expert on anything but makes himself out to be an expert on everything… knows nothing about art or sailing or anything.

I loved it, readable, funny, and entertaining; I just love the way he writes.

The idea is that because it is put in a comic way, it is acceptable – but it is not.

Just crummy humour and behaviour

Wildly self-indulgent writing

An indictment of Twain’s lack of any interesting vision

I appreciated the close-up of 19th century European history witnessed at first hand and brought to life.

He has a wonderful sense of irony.

He’s a hypocrite.

I liked the book very much; I like books about travel.

His damnation of biblical Christianity is devastating.

I feel guilty because I think I enjoyed it more than everyone in the group.

Twain is an early stand-up comic.

So the question to be addressed is: how is it that an internationally-revered author excites such diverse and fervent views amongst our members?

A tentative answer might be that we shouldn’t judge Twain just by The Innocents Abroad.

Mark Twain, a short biography

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, known to the world as Mark Twain, was born on 30 November, 18354, in the small town of Florida, Missouri. When he was four, the Clemens family moved 35 miles east to the town of Hannibal, a frequent stop on the Mississippi for steam boats arriving by both day and night from St. Louis and New Orleans.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, known to the world as Mark Twain, was born on 30 November, 18354, in the small town of Florida, Missouri. When he was four, the Clemens family moved 35 miles east to the town of Hannibal, a frequent stop on the Mississippi for steam boats arriving by both day and night from St. Louis and New Orleans.

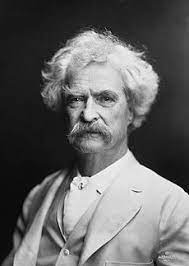

Clemens’s father John Clemens worked as a storekeeper, lawyer, judge, and land speculator, dreaming of wealth but never achieving it. When Clemens was 12, his father died of pneumonia. At 13, he needed to earn his keep, so he found employment as an apprentice printer at the Hannibal Courier, which paid him with a meagre ration of food. This portrait shows Clemens, aged 15, holding a printer’s composing stick with the letters SAM.

In 1851, at 15, he got a job as a printer and occasional writer and editor at the Hannibal Western Union, a little newspaper owned by his brother. It was here that young Clemens found he enjoyed writing.

At 17, he left Hannibal behind for a printer’s job in St. Louis. Then, in 1857, 21-year-old Clemens fulfilled a dream: he began learning the art of piloting a steamboat5 on the Mississippi. A licensed pilot by 1859, he soon found regular employment plying the shoals and channels of the great river. He loved his career—it was exciting, well-paid, and high-status, roughly akin to flying a jetliner today. However, his service was cut short in 1861 by the outbreak of the Civil War, which halted most civilian traffic on the river.

At 17, he left Hannibal behind for a printer’s job in St. Louis. Then, in 1857, 21-year-old Clemens fulfilled a dream: he began learning the art of piloting a steamboat5 on the Mississippi. A licensed pilot by 1859, he soon found regular employment plying the shoals and channels of the great river. He loved his career—it was exciting, well-paid, and high-status, roughly akin to flying a jetliner today. However, his service was cut short in 1861 by the outbreak of the Civil War, which halted most civilian traffic on the river.

Clemens began working as a newspaper reporter for several newspapers all over the United States. In July, 1861, he climbed on board a stagecoach and headed for Nevada and California where he would live for the next five years. At first, he prospected for silver and gold but after this failed, in September 1862, he went to work as a reporter for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise. He churned out news stories, editorials, and sketches and, along the way, adopted the pen name “Mark Twain”.

Clemens’ pseudonym, Mark Twain, comes from his days as a river pilot. It is a river term which means two fathoms or 12-feet when the depth of water for a boat is being sounded: “Mark twain” means that is safe to navigate6.

In 1870 Clemens married Olivia Langdon and they had four children, one of whom died in infancy and two of whom died in their twenties. Their surviving child, Clara, lived to be 88. Her only daughter died without having any children, so there are no direct descendants of Samuel Clemens living.

Twain became one of the best known storytellers in the West. He honed a distinctive narrative style—friendly, funny, irreverent, often satirical and always eager to deflate the pretentious.

Twain began to gain fame when his story, The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calavaras County appeared in the New York Saturday Press on November 18, 1865. Twain’s first book, The Innocents Abroad, was published in 1869, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer in 1876, and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in 1885. All together, he wrote 28 books and numerous short stories, letters and sketches.

Twain’s last fifteen years were filled with public honours, including degrees from Oxford and Yale. Probably the most famous American of the late 19th century, he was much photographed and applauded wherever he went. He carefully cultivated his image, generally appearing in his signature white suit.

He was one of the most prominent celebrities in the world, travelling widely overseas, including a successful round-the-world lecture tour in 1895-96, undertaken to pay off his debts.

Clemens died at age 74 on April 21, 1910, at his country home in Redding, Connecticut. He was buried in Elmira, New York7.The Mark Twain & Ossip Gabrilowitsch Monument.8 (left) stands near the graves of Mark Twain, his wife Olivia, their daughter Clara and her husband, the Russia-born concert pianist, Ossip Gabrilowitsch. The shaft of granite, which supports the bas-reliefs of Mark Twain and his son-in-law, is 12 feet high, or rather 2 fathoms, the physical equivalent of the navigation term ‘mark twain’

The Book

According to the cover of one edition, The Innocents Abroad is

Mark Twain’s irreverent and incisive commentary on the “New Barbarians” encounter with the “Old World”.

Published in 1869, it chronicles what Twain called his Great Pleasure Excursion – a five-month sea cruise – on board the chartered vessel Quaker City (formerly USS Quaker City) through Europe and the Holy Land with a group of American travellers in 1867.

Twain in 1867, possibly taken in Constantinople.

Twain in 1867, possibly taken in Constantinople.

In early 1867 Twain convinced the Daily Alta newspaper to provide $1,250 (the equivalent of $20,000 today) to pay his fare on the Quaker City tour of Europe and the Middle East. Throughout the five-month trip, Twain sent 51 letters to the Alta, which the paper published between 2 August 1867 and 8 January 1868 under the running heading: The Holy Land Excursion. Letter from ‘Mark Twain.’ Special Travelling Correspondent of the Alta. These letters, together with seven printed in two New York papers, became the basis for The Innocents Abroad.9

When published in 1869, The Innocents Abroad was sold as a subscription book.10

What did we think of the book?

It would be relatively easy to create a list, with copious supporting examples, of aspects of the book and Twain that members disliked. This list would include Twain’s apparent racism and bigotry; his general lack of empathy with people of from other countries; his mockery of art and architecture; his lampooning of religion and religious practices in general; his lack of engagement with the countries he visits and the people he encounters; his willingness to turn everything into a cheap joke; and his wildly self-indulgent language.

It is a little harder to create a list of aspects of the book and Twain that members actually liked. Though shorter, this list would include Twain’s ability and willingness to “tell it how it is”, or at least how he sees it (rather than how others have seen it before him); his tendency to be an iconoclast, debunking views of art and religion; his even-handedness, lampooning himself, his fellow-passengers, and his own country as mercilessly as any others; his use of language, deftly mixing sentences of baroque proportions with short, pithy observations; above all, his irony and his robust sense of humour.

On Travelling Generally

Commenting on Twain’s repeated complaints that he and his party are cheated by the locals and their succession of guides (all renamed Ferguson), someone said that this is exactly what happens the world over, particularly to tourists who choose not to engage with the people they encounter. He cited the people who offer camel and donkey rides around the Pyramids.

Another person noted how, also travelling in Egypt, she felt she was “handed over” at each stage in her journey from one person to another ready to exploit her; she felt she was “always in someone’s commercial embrace”.

On the whole business of travel writing, one person said that one should be wary of writing too hastily about the country one is visiting. Only after an extended period should one feel confident about making comments. However if all one can say is critical and negative, then perhaps it is best to refrain from going to print. Another said this phenomenon is still around today: “you go somewhere for two minutes and then you write a book about it.”

Twain’s “failing may be confusing what they did with what was interesting”; a list of what they did does not tell us much about the places visited and, in this case demonstrated “a lack of any interesting vision” which a good writer could bring to such a tour.

Twain and Art

A related area which revealed differing views was Twain’s attitude towards art. In the France and Italy especially, he made what was, for some group members, quite scurrilous remarks about the Old Masters in the famous galleries they visited. Thus, some felt, he was revealing his total ignorance about art.

We visited the Louvre … and looked at its miles of paintings. Their nauseous adulation of princely patrons was more prominent to me … than the charms of colour and expression which are claimed to be in the pictures.

We have seen famous pictures until our eyes were weary looking at them.

Writing about da Vinci’s The Last Supper, he noted that people

come here from all parts of the world and glorify this masterpiece. They stand entranced before it with bated breath and parted lips, and when they speak, it is only the catchy ejaculations of rapture:

Oh Wonderful

Such grace of attitude

Such faultless drawing,

Such matchless colouring

What delicacy of touch

A vision! A vision!

I only envy these people; I envy them their honest admiration, if it be honest; their delight, if they feel delight.

But he wonders

How can they see what is not visible?

I am willing to believe that the eye of the practiced artist can rest upon the Last supper and renew a lustre where only a hint of it is left, supply a tint that has faded away…. But I cannot work this miracle.

Of portrayals of saints and martyrs, he confesses

It seemed to me that when I had seen one of these martyrs I had seen them all.

Several of us agreed with him on that one. There was sympathy with his tendency to resist judging famous paintings and artists through the eyes of other people. One member said she sometimes found herself at odds with friends regarding particular works of art and felt vindicated by some of Twain’s remarks on art.

Twain and Religion

If Twain seeks to be a debunker of art and some architecture, he reserves much harsher criticism for all forms of organised religion. He is nothing if not even-handed in his condemnation. His attack on the Roman Catholic Church, its beliefs, its practices and holy relics, is relentless; he is equally ruthless with his comments on the Protestants represented in his fellow travellers; he is extremely rude about the practices of Islam; and when they are mentioned, he is just as forthright about Jews.

He reserves special scorn for his fellow passengers who put observation of the Sabbath above compassion for the horses that transport them to Damascus, a journey which would normally take three days but which they were obliged to do in two days because “three of our pilgrims would not travel on the Sabbath.”

We pleaded for the tired, ill-treated horses and tried to show that their faithful service deserved kindness in return and their hard lot, compassion. But whenever did self-righteousness know the sentiment of pity.

Twain is particularly scathing about holy sites, wells, caves, pits, any location associated with a story from the bible. Here are some of his deeply cynical comments about grottos:

It seems curious that personages intimately connected with the Holy Family always lived in grottoes – in Nazareth, in Bethlehem, in imperial Ephesus – and yet nobody in their day and generation thought of doing anything of the kind. …. when the Virgin fled from Herod’s wrath, she hid in a grotto…. the slaughter of the innocents in Bethlehem was done in a grotto, the Saviour was born in a grotto. It is exceedingly strange that these tremendous events all happened in grottoes – and exceedingly fortunate because the strongest houses must crumble to ruin in time, but a grotto in living rock will last forever.

He states that

it is an imposture – this grottos stuff – but one that all men ought to thank the Catholics for. The world owes the Catholics its good will even for the happy rascality of hewing out these bogus grottoes in the rock.

Not only does he mock stories in the Bible, he even invents his own 1621 edition of the Apocryphal New Testament, from which he quotes at will:

Chapter 16. Christ miraculously widens or contracts gates, milk-pails, sieves or boxes, not properly made by Joseph, he not being skilful at his carpenter’s trade.

He is no more convinced about angels:

The very scene of the Annunciation – an event which has been commemorated by splendid shines all over the world…. I could sit off several thousand miles and imagine the angel appearing… but few can do it here. I saw the little recess from which the angel stepped but could not fill its void. The angels I know are creatures of unstable fancy – they will not fit in niches of substantial stone. Imagination labours best in distant fields.

With his unremitting cynicism about religion, one member wondered about Twain’s own religious beliefs. It seems that whilst he was notionally a Presbyterian, he grew ever more critical of organised religion. On the other hand, he raised money to build a Presbyterian Church in Nevada in 1864, although it has been argued that it was only by his association with his Presbyterian brother that he did that.

Probably the most telling indicator of his views was not available to the world until his biography was published in November 2010 (one hundred years after his death). In it he states:

Ours is a terrible religion. The fleets of the world could swim in spacious comfort in the innocent blood it has spilled.11

What is there to like about Twain?

Despite the strongly critical views held by perhaps the majority of the group, there were those who found good things to say about Twain and his work.

One of the most telling points to be made during our discussion was that, although Twain is justly regarded by many as the father of the great American novel, this reputation is not justified by The Innocents Abroad. Rather the two novels upon which his fames squarely rests are Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn.

One American member had attended several times performances of Mark Twain Tonight by Hal Holbrooke and would do so again given the chance. He was certain that The Innocents Abroad was in no way representative of his writing. In his view Twain was capable of great insight, and great humour, without being hurtful; but not in this novel.

Towards the end of the meeting he read out two passages by Twain. The first was from early chapters of Huckleberry Finn and the second from Twain’s famous piece on James Fennimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses. Both passages delighted everyone present.

One member said that, after listening to the excerpts, she did not recognise the author of those as being the same person who wrote The Innocents Abroad.

On the other hand, several members found Twain’s writing very amusing.

One said that although he was unkind about places and people, he was so outrageous he was funny. Another said that she admired his sense of irony and saw, in his remarks about religion, hints of the irreverent satire of biblical films and epics, Monty Python’s Life of Brian.

She also appreciated the first-hand accounts of history in the making. She had studied 19th century European history at school and Twain’s account of seeing Napoleon III in Paris or the Tsar in Odessa brought the subject to life.

One member felt guilty, having heard the critical comments of others, saying that he had probably enjoyed the novel more than anyone else in the group.

He quoted the frontispiece to the 1869 edition:

THE

INNOCENTS ABROAD

Or

THE NEW PILGRIMS’ PROGRESS

BEING AN ACCOUNT OF THE STEAMSHIP QUAKER CITY’S

PLEASURE EXCURSION TO EUROPE AND THE HOLY LAND;

WITH DESCRIPTIONS OF COUNTRIES, NATIONS, INCIDENTS

AND ADVENTURES, AS THEY APPEARED TO THE AUTHOR

He felt that the telling words were as they appeared to the author. As if to emphasise the point, in the preface Twain reminded the reader

This is a record of a pleasure trip; it is not a record of a solemn scientific expedition;

If it (the record) has a purpose, it is to suggest to the reader how he would be likely to see Europe and the East if he looked at them with his own eyes instead of the eyes of those who travelled in those countries before him.

And if THAT were not enough warning, Twain offered

no apologies for any departures from the usual style of travel-writing that may be charged against me – for I think I have seen with impartial eyes, and I am sure I have written at least honestly, whether wisely or not.

According to this member, Twain might have added “So you have been warned”. In the view of this member, to use a current phrase, “what you get is what it says on the tin.”

Why did Twain pick on the Turks?

Many members of the group felt that Twain was especially unkind to Turks, that in some way he was picking on them. We wondered why.

One person suggested that he was merely reflecting the attitudes of the times. Part of the reason may have been that, at the time of Twain’s journey, a lot of things were going on that involved Turks. In particular, the power and prestige of the Ottoman Empire was in serious decline and “the knives were out” for this imperial power that had concerned Europe for over 400 years.

Indeed the Eastern Question had been raised many times during the Empire’s long, slow decline from its sixteen century greatness. Put simply, the question was what happens if the Ottoman Empire falls?

The Western Powers and Russia all had vested interests in this question. Russia in particular had long nursed a desire to have free access to the Bosporus and thus the Mediterranean. The Russian Tsar Nicholas seemed particularly keen to hasten the Empire’s demise. He broached the Eastern Question with the British Government during a visit in 1844, and in informal conversations with the British Ambassador in St Petersburg in 1853, he made clear his view of the stage of the Empire. He concluded:

We have a sick man on our hands – a man gravely ill.

Months later he had precipitated the Crimean War, which led to the defeat of Russia by the joint forces of the Ottoman Empire, British Empire, and France. It ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1856, nine years before Twain made his trip.

However, the Eastern Question had not gone away and European attitudes to the Ottomans were anything but stable.

At the beginning of the 19th century, encouraged by the very significant reforms instituted by Mahmud II, Western attitudes became much friendlier. This continued into the early reign of Mahmud’s successor, Sultan Abdul Mecid, particularly after he trumpeted the Tanzimat reforms in 1839, encapsulating many of the farsighted visions of his predecessor.

The intention to reform was reiterated in 1856 as a bid to gain credibility in the Treat of Paris negotiations, but by 1860 the early promises of Abdul Mecid were viewed with scepticism and the Ottoman’s star was again waning in the views of the West.

One incident contributing to this declining view was the alleged role of the Ottoman authorities in what became known as the Druze-Maronite massacre in Lebanon for which some European states pointed the finger of blame – possibly unfairly – at the Ottoman who controlled the area at the time. This is mentioned specifically by Twain in The Innocents Abroad and obviously contributed to his apparently anti-Turkish views.

A further element which was contributing to the generally negative attitude towards the Ottomans was more strident independent Greece and the growth of the Megalia Idea13, first mentioned in 1844 and gaining support covertly at least by Britain in the 1860s. By its nature, it was anti-Turk, generating animosity to the Ottomans.

Another explanation could be that every era has had its popular “bogeyman”, often invoked irrationally and blamed for everything.

The Illustrious Convalescent was published on 20th June 1867 during the visit of Sultan Abdülaziz to Britain and makes a direct reference to Tsar Nicholas’s “sick man” comment. Turkey Limited was published almost 30 years later on 28 November 1896, during the reign of Sultan Abdül Hamid when the Empire had been overwhelmed by its enormous debts to Britain and France. The Ottoman plan was to restructure the foreign debt by issuing five year Government bonds in lieu of repayment of interest.

The Illustrious Convalescent was published on 20th June 1867 during the visit of Sultan Abdülaziz to Britain and makes a direct reference to Tsar Nicholas’s “sick man” comment. Turkey Limited was published almost 30 years later on 28 November 1896, during the reign of Sultan Abdül Hamid when the Empire had been overwhelmed by its enormous debts to Britain and France. The Ottoman plan was to restructure the foreign debt by issuing five year Government bonds in lieu of repayment of interest.

It is certainly clear that the popular press thought it was acceptable to take a patronising and mocking attitude to Turkey at that time.

Without condoning it, in the light of the events of the 1860s and the prevailing attitudes, perhaps it is not surprising to find the Twain joins in the general denigration of the Turks as the possible bogeyman of the day.

Was Twain serious at all?

One possible reading of the novel is that it was a complete satire on the American Abroad. Some contemporary critics seemed to take this view. For example after a fairly scathing critique of the novel, the British Saturday Review of 8 October 1870 concludes:

Perhaps we have persuaded our readers by this time that Mr Twain is a very offensive specimen of the vulgarest kind of Yankee. And yet, to say the truth, we have a kind of liking for him. There is a frankness and originality about his remarks which is pleasanter than the mere repetition of stale raptures; and his fun, if not very refined, is often tolerable in its way. In short, his pages may be turned over with amusement, as exhibiting more or less consciously a very lively portrait of the uncultivated American tourist, who may be more obtrusive and misjudging, but is not quite so stupidly unobservant as our native product. We should not choose either of them for our companions on a visit to a church or a picture-gallery, but we should expect most amusement from the Yankee as long as we could stand him.

Another review that points in this direction appeared in an American monthly magazine called The Galaxy, in December 1870. The article is too long to quote here but towards the end of a devastatingly critical review, the writer makes the following comment:

That the book is a deliberate and wicked creation of a diseased mind, is apparent upon every page.14

On closer reading one realises that the reviewer is none other than Twain himself, writing a parody of reviews of his book. Perhaps this, above all, is an indication that he never intended this book to be taken at all seriously.

1 The Ballad of East and West by Rudyard Kipling

3 The official Mark Twain website:http://www.cmgww.com/historic/twain/index.php

4 He was born in the year that Haley’s comet passed close to earth; he died, as he forecast, 75 years later when the comet returned.

5 For more on steamboats seehttp://www.twainquotes.com/Steamboats/SteamboatCareer.html where this picture comes from. Colour photograph of apprentice Clemens http://steamboattimes.com/images/mark_twain/slc_1850dec_colour_printersapprentice288x360.jpg

6 Twain is anarchaic term for “two”, as in “The veil of the temple was rent in twain.” The river-boatman’s cry was “mark twain” or, more fully, “by the mark twain”, meaning “according to the mark [on the line], [the depth is] two [fathoms],” that is, “The water is 12 feet (3.7 m) deep and it is safe to pass.”http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Twain

7 Biography compiled from the Official Mark Twain websitehttp://www.cmgww.com/historic/twain/index.php and http://www.biography.com/people/mark-twain-9512564?page=1 where more information is available

9 http://twain.lib.virginia.edu/innocent/altahome.html. This site also has a selection of the original letters and compares them with the book version. One letter– on nude bathing in Odessa – was omitted from the book altogether on the grounds, presumably, of being too scandalous. But you can read it here http://twain.lib.virginia.edu/innocent/alta22.html

10 In 19th century America, there were two ways to sell new books: door-to-door by subscription or in a retail store. An average subscription book cost $5.00 to $7.00. Retail books cost about $3.50. Books that were sold by subscription were not available in retail bookshops. They were “often long, running 600 to 700 pages, to give readers ‘their money’s worth’.http://historyofbooks.wordpress.com/a-brief-history-of-the-personal-memoirs-of-u-s-grant/late-19th-century-bookmaking/ from Friedman, W. A. (2004). Selling U.S. grant’s memoirs: The art of the canvasser. Birth of a salesman: The transformation of selling in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

12 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F_rTMNnxwSE for a taste of the Hal Holbrooke show

13 A concept of Greek nationalism that expressed the goal of establishing a Greek state that would encompass all ethnicGreek-inhabited areas, including the large Greek populations that after theGreek independence in 1830, still lived under Ottoman occupation.