From the Holy Mountain

From the Holy Mountain

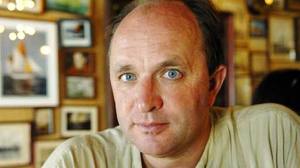

by William Dalrymple

Dalrymple’s journey in the shadow of Byzantium starts at the Monastery of Iviron, Mount Athos, Greece, on 29 June 1994, the feast of Saints Peter and Paul. Inspired by The Spiritual Meadow he is to follow in the steps of the author John Moschos, a 6th century traveller monk. The journey takes him from Mount Athos to Constantinople and Anatolia, then southwards to the Nile and thence to the Great Kharga Oasis in Egypt, once the southern frontier of Byzantium.

Ostensibly From The Holy Mountain is a travel book, ‘combining flashes of lightly-worn scholarship with a powerful sense of place and the immediacy of the best journalism’ according to one reviewer. However, the author digs deep to present his view of the ‘downtrodden’ Christians in the Middle East and to show how the land which saw the birth of Christianity and which, in Byzantine times was almost exclusively Christian, is now almost devoid of any Christian presence.

His stated mission was to “do what no future generation of travellers will be able to do:

- See what John Moschos (the Abstemious) and his companion Sophronius (the Sophist) saw

- Sleep in the same monasteries

- Pray under the same frescoes and mosaics

- Discover what is left of his world

He concludes that he is witnessing “What is in effect the last ebbing twilight of Byzantium”.

The Reading Group discussed the book twice, because some members had not been able to finish the book by the earlier meeting.

For some members, the book challenged their knowledge of the detailed history of the period covered in this work. Our notions of Byzantium, the growth of the empire and the spread of Christianity were sometimes found wanting.

One member found the following website Euratlas Antique Maps useful for the maps of Europe which it provides, showing the waxing and waning of the various empires which have held sway over Europe during the past 2000 years or so.

The following four maps are particularly useful for an overall view of the rise and fall of the Byzantine Empire, and its successor the Ottoman Empire.

Euratlas Periodis Web – Map of Roma in Year 100

Euratlas Periodis Web – Map of Roman Empire in Year 600

Euratlas Periodis Web – Map of Roman Empire in Year 1400

Euratlas Periodis Web – Map of Ottoman Sultanate in Year 1400

Side note on Byzantium, the growth of the Byzantine Empire and Spread of Christianity

Byzantium was alleged to have been established in the 7th century BC by Byzans from Megara who was sent there on the advice of the oracle at Delphi. He recognised it as the ideal site for a city, easily defensible with sea on two sides and a perfect harbour. The original settlement was tiny. For those who know SultanAhmet, it occupied the area now covered by Topkapi palace and Gulhane Park. Its outer limit was just beyond where the Hippodrome stood.

As the Roman Empire spread eastwards, and particularly once the western region based in Rome began to decline, it was expedient to move the locus of power to a more central location and Byzantium, soon to be renamed Constantinople, fitted the bill. Strategically well placed, eminently defensible, it became New Rome.

Expanded by Constantine, Justinian and Theodosius to the line of the ancient Theodosian walls, it proved its strategic strength by withstanding all sieges until 1453.

The conversion of Constantine to Christianity, and particularly the efforts of his mother in Jerusalem, ensured that Christianity spread along with the growing Empire.

The journey of John Moschos, which provides the guide for William Dalrymple’s own odyssey, took place at the height of the Byzantine Empire, and just before the birth of Islam.

Some were surprised to learn how sophisticated life in the Byzantine Empire was when north west Europe was still in the Dark Ages.

Views of Reading Group to this book

The book brought out a number of views amongst the members:

- One member read half the book, omitting the pages that ’were too political, religious or historic. On the other hand, he said, I was very interested in the street life and the recent history of the various countries. It is interesting how the human race is killing, torturing, giving pain to each other from the very beginning and it goes on and on, and it happens in the ‘Holy Land’(!) From The Holy Mountain is a valuable resource for the people who are keen on such subjects.’

- This comment led the group to contrast the famous tolerance shown by the Ottoman Empire for almost all of its existence with the present day situation at the heart of the Holy Land, Jerusalem. Not only is the city divided along Jewish and non-Jewish lines, but also the various branches of Christianity are divided amongst themselves. The irony of having a Muslim holding the keys to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was not lost on the group Muslim family holds key to sacred sepulchre / For centuries, their ancestors have opened door to church where Jesus believed buried – SFGate

- The group noted that William Dalrymple is at pains to emphasise the centuries of tolerance show to religious minorities by Islam. Nowhere was this more evident that in Constantinople. He notes a Huguenot writing in the 17th century, “When every capital in Europe was ablaze with burning heretics, there is no country on earth where the exercise of all religions is more free and less subject to being troubled than in Turkey”. (For a detailed exposition of religious tolerance in Ottoman times see:

- John Freely, Istanbul, The Imperial City;

- Philip Mansel, Constantinople, City of the World’s Desire

- Lord Kinross, The Ottoman Centuries)

- Several members of the group recalled examples of religious tolerance in earlier times in this region. One mentioned how she, as a Muslim, regularly visited Orthodox churches in her neighbourhood in Istanbul. Recalling the race riots in Istanbul in 1955, she noted how multi cultural and multi-faith Istanbul used to be. Syriacs, Syrian Christians, were renowned in the Covered Bazaar as jewellers.

- One point that members found interesting was the concept of syncretism, the use by members of different faiths of each other’s places of worship and holy shrines. Some found echos of “Birds Without Wings” where both Christian and Muslim villagers had faith in the powers of oil passed over the bones of a Muslim saint, or the lighting of candles in the church. Syncretism is still observed today, for example at Meryemana, the House of the Virgin Mary at Selçuk which both Muslims and Christians regard as a holy shrine.

- Another notable point arising from the book was the similarities between early Christian devotional practices and those of Islam:

- Bowing and prostration

- Minarets deriving from square, late antique period Syrian church towers

- Islamic mysticism and Sufism derived from Byzantine holy men and desert fathers

- The prayer niches in early Byzantine churches and the cells of monks which translate into the Mihrab in the mosques

- And, of course, the common roots of the Prophet Abraham, and the adoption of much of the Old Testament of the Bible, recognition of Jesus as a Prophet and of Mary.

- This observation prompted one member to draw comparisons with Jewish religious observance, including, for example, the eating of helva after prayer.

- Others considered the origins of the rituals observed by the various faiths, some suggesting that they all have a common root in Buddism or maybe the Aztec culture.

- One member roundly criticised the book and its author for expressing extremely biased and uninformed views regarding the current (1994) position of the Christians he met in Turkey. She wondered where he had got his information from and doubted he had been very thorough with his research.

- Another member argued that Dalrymple was relating his experiences from the viewpoint of a practising Roman Catholic.

- Other members had found the book a fascinating read which painted wonderful images of a twentieth-century landscape bedevilled by the conflicts of the past.

- At the time the group was meeting, the so-called Arab Spring was taking place in the region. Whilst it is not specifically religious in its origins, the wave of popular uprising may yet change the predictions Dalrymple makes towards the end of his book, but in what direction only a very brave person would hazard to guess.

From the Holy Mountain

From the Holy Mountain