One evening in early October an exclusive group of eleven boarded a winged horse and flew to Ankara and from there embarked upon a 1,300 km journey lasting four days.

Ankara is a new city, chosen by Atatürk for its central position and given fine government buildings during the 1920s and ’30s. Since then it has suffered urban sprawl and now has a current population of four million.

Twice capital of Turkey in antiquity – known as Ankyra under the Romans, as Angora in Ottoman times – Ankara is a neglected modern capital, still ignored by those who, when it comes to history, are in the habit of skipping from the Hittites to the new republic. But at last a long-postponed renaissance is occurring. Recent discoveries in Ulus – old Ankara – have awakened a desire to pull together the missing threads. The Museum of Anatolian Civilisations is no longer the sole attraction: changes in and around the ancient Citadel are now complemented by boutique hotels.

Although Hittite remains dating back to before 1200 BCE have been found in Ankara, the town was really a Phrygian foundation that prospered at the intersection of the north-south and east-west trade routes. Later it was taken by Alexander the Great, claimed by the Seleucids and finally occupied by the Galations who invaded Anatolia around 250 BCE. Augustus Caesar annexed it to Rome in 25 BCE as Ankyra.

The Byzantines held the town for centuries, with intermittent raids by the Persians and Arabs. When the Seljuk Turks came to Anatolia after 1071, they took the city but held it with difficulty.

Ottoman possession of Angora did not go well for it was near here that Sultan Yıldırım Beyazit was captured by Tamerlane, and later died in captivity. After the Timurid state collapsed and the Ottoman civil war ended, Angora became a quiet backwater, famous only for its goats.

When Atatürk set up his provisional government in 1920, it was a small dusty settlement of some 30,000 people, strategically sited at the heart of the country. After his victory in the War of Independence, Atatürk declared it the new Turkish capital (October 1923), and set about developing it. European urban planners were consulted, and the result was a city of long, wide boulevards, a forested park with an artificial lake, and numerous residential and diplomat neighbourhoods. From 1919 to 1927 Atatürk never set foot in Istanbul, preferring to work at making Ankara the country’s capital in fact as well as in name.

Day one

On arrival at Ankara airport we boarded our bus and, guided by our own Arif Vidinli, we were treated to an overview of the city by driving through Ulus and Kızılay to our hotel in Çankaya where, refreshed after a night’s sleep we were ready the next morning for a full day’s sightseeing. Our guide, Suat Dingil, took us first to Anıt Kabir, Atatürk’s mausoleum. It stands in a park on top of a small hill. Our guide explained that all the civilisations that had existed in Turkey were represented in the building – Hittite windows with Phrygian lattice work for example.

The massive courtyard of the tomb is walled by colonnaded walkways and rooms displaying memorabilia and personal effects of Atatürk. Past the colonnade on the left and right are gilded inscriptions and quotations from Atatürk’s speech celebrating the republic’s 10th anniversary in 1932. A lofty hall is lined in marble and sparingly decorated with mosaics. At the northern end stands an immense marble cenotaph, cut from a single piece of stone. Atatürk’s actual tomb is beneath it. Building started in 1944 and the mausoleum took nine years to complete. The high-stepping ceremonial guards are crack troops recruited from the three branches of the military service.

|  |  |

Our next stop was the Museum of Anatolian Civilisations, Ankara’s premier attraction. It is housed in a restored 15th century covered market (bedesten). Displays are divided into Anatolian civilisations: Palaeolithic, Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Bronze Age, Assyrian, Hittite, Phrygian, Urartian and Lydian as well as the later Greek and Roman artefacts. Before entering the museum Suat explained the history of these civilisations in exquisite detail.

|  |  |

Just up the hill from the museum is the Citadel (Ankara Kalesı). Here was the perfect stop for lunch because within the citadel a growing number of old houses are being converted into similar, atmospheric restaurants. Reputedly the best of the lot is the Zenger Paşa Konağı with its authentic Ottoman cuisine and that is where our guide took us.

|  |  |

After lunch we strolled around the Citadel which took its present form in the 9th century when the Byzantine emperor Michael III constructed the outer walls. The inner walls date from the 7th century. During an administrative reshuffle in 1522, the Citadel was separated from the Ottoman town. Until the First World War it continued to be the Christian quarter where some of the konaks of Armenian merchants, who dealt initially in mohair and later in cotton, still survive.

Perhaps unique in Anatolia the Citadel continues to function as intended, providing shelter for a large section of the city’s shifting populations. The upheavals of the last decades of the 19th century, the First Balkan War in 1912, and the aftermath of the First World War affected all the ethnic communities crammed into the maze of alleys, connecting gardens and now-decaying merchant houses. But despite all this, and modern attempts to tidy it up, a village atmosphere survives.

|  |  |

After our stroll some of us shopped and some of us had a coffee outside the Çukurhan, a 17th century shopping mall, which had remained in continuous use until the building caught fire in 1950, now a meticulously restored boutique hotel, the Divan Çukurhan.

It was time to leave Ankara and travel 200 kilometres to our next destination, Hattuşa, the capital city of the Hittites.

The Hittites were a people who commanded a vast middle eastern empire, conquered Babylon and challenged the Egyptian pharoahs over 3000 years ago. There were few clues to their existence until 1834 when a French traveller, Charles Texier, stumbled on the ruins of the Hittite capital of Hattusa, next to the village of Boğazköy (today called Boğazkale).

In 1905 excavations began and turned up notable works of art, most of them now preserved in Ankara’s Museum of Anatolian Civilisations. Also brought to light were the Hittite state archives, written in cuneiform on thousands of clay tablets. From these tablets, historians and archaeologists were able to construct a history of the Hittite Empire.

Speaking an Indo-European language, the Hittites swept into Anatolia around 2000 BCE, conquering the Hatti from whom they borrowed both their culture and name. They established themselves at Hattuşa, the Hatti capital, and in the course of a millennium enlarged and beautified the city. From about 1375 to 1200 BCE, Hattuşa was the capital of a Hittite Empire that, at its height, incorporated parts of Syria as well.

The Hittites worshipped over a thousand different deities but among the most important were Teshub, the storm or weather god, and Haptu, the sun goddess. The cuneiform tablets revealed a well-ordered society with more than 200 laws.

From about 1250 BCE the Hittite Empire seems to have gone into a decline, its demise hastened by the arrival of the Phrygians. Only the city-states of Syria survived until they, too, were swallowed by the Assyrians.

Day two

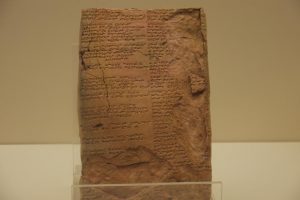

After breakfast we set off to explore Hattuşa. We paused at the entrance to the site to study The Treaty of Kadesh. This is the earliest known peace treaty and was concluded between the Hittite King Hattusili III and the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II in 1269 BCE. It was written on a clay tablet and discovered at Boğazkale in 1906.

Until then only the text of this treaty, carved on a stele in the Egyptian Temple of Karnak in Egyptian hieroglyphs, was known. The tablet had many missing pieces and contained only about half of the text. During later excavations, four pieces belonging to the main text were found and the missing parts were completed. The text of the treaty reads:

“It is concluded that Reamasesa-Mai-amana (the cuneiform transcription of Ramesses II) , the Great King, the king (of the land of Egypt) with Hattusili, the Great King, the king of the land of Hatti, his brother, for the land of Egypt and the land of Hatti, in order to establish a good peace and a good fraternity forever among them.

“If domestic or foreign enemies marches against one of these two countries and if they ask help from each other, both parties will send their troops and chariots in order to help.

“If a nobleman flees from Hatti and seeks refuge in Egypt, the king of Egypt will catch him and send back to his country.

“If people flee from Egypt to Hatti or from Hatti to Egypt, those will be sent back. However, they will not be punished severely, they will not shed tears and their wives and children will not be punished in revenge.”

As it is the first written peace treaty in the history, a two-metre long copper copy of the original tablet was hung on a wall of the United Nations building in New York. Closer to home the original tablet can be viewed in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum.

Hattuşa was once a great and impressive city defended by stone walls over six kilometres in length. Today the ruins consist mostly of reconstructed foundations, walls and a few rock carvings, but there are several more interesting features, including a tunnel and some fine hieroglyphic inscriptions preserved in situ.

|  |  |

|  |  |

We spent three hours exploring the site before moving on to Yazılıkaya. Yazılıkaya translates as ‘Inscribed Rock’ and that’s exactly what we found there. The place had long been a Hittite religious sanctuary: in later Hittite times (13th century BCE) a monumental gateway and temple structure were built in front of the galleries. There are two natural rock galleries. The larger one contains low reliefs of numerous goddesses and pointed-hatted gods marching in procession. The heads and feet of most of the figures are shown in profile but the torso is shown front on. This is a common feature of Hittite relief art. The narrower gallery has the best preserved carvings and is thought to be the burial place of King Tudhaliya IV (1250-1220 BCE) and his family.

|  |  |

Now it was time to sample some Hittite food. We made our way to a lokanta where a typical Hittite meal had been prepared – lentil soup followed by lamb stew. (Visit the Turkish cuisine category on this website for an example of a Hittite recipe.)

After lunch we just had time to visit Boğazkale’s excellent small museum before embarking on the long drive to Amasya.

|  |  |

Set in a rocky ravine with the Yesilirmak river running through it, Amasya is regarded as one of the prettiest towns in all Turkey and is famous for its apple production.

Capital of the modern province of the same name, Amasya was also once the capital of a great Pontic kingdom. Its dramatic setting complements its numerous historic buildings, especially the rock-hewn tombs of the kings of Pontus and some fine old mosques and medreses together with many picturesque Ottoman half-timbered houses, especially along the north bank of the river.

Once a Hittite town, Amasya was conquered by Alexander the Great, and then became the capital of a successor-kingdom ruled by a family of Persian satraps. By the time of King Mithridates II (281 BCE), the Kingdom of Pontus was entering its golden age and dominated a large part of Anatolia.

During the latter part of Pontus period, Amasya was the birthplace of Strabo (c 63 BCE to CE 25), the world’s first historian. Strabo left home to travel in Europe, west Asia and north Africa, writing 47 history and 17 geography books. Though most have been lost, we know something of their content because many other classical writers chose to quote him.

Amasya’s golden age ended when the Romans decided it was time to take over all of Anatolia (47 BCE). After them came the Byzantines, who left little mark on the town, the Seljuks (1075) and the Mongols (mid-13th century). In Ottoman times, Amasya was an important base when the sultans led military campaigns into Persia. By tradition the Ottoman crown prince had to be taught statecraft in Amasya, and test his knowledge and skill as governor of the province.

After WW1 Atatürk came to Amasya where he secretly met with friends on 12 June 1919 and hammered out basic principles for the Turkish struggle for independence.

Our party arrived before sunset and had time to visit Amasya’s principal mosque, Sultan Beyazit II Camil (1486), and take a walk along the river. We checked into the Harsena Hotel which is squeezed between the railway line (trains run all night exploding out of a nearby tunnel) and a bar playing loud music until the early hours. However we managed to get up in time the next morning to visit Amasya’s small museum. Among the interesting exhibits are the wooden doors of the Gökmedrese Camii, the Roman coin minted in Amasya, the strange baked-clay coffins and some gruesome mummies dating from the 14th century.

|  |

Day three

It was time to move on again, west to Safranbolu with a stop for lunch at the Ilgaz Mountain Resort.

If it were simply a well-preserved collection of Ottoman houses, Safranbolu could not claim to be unique. But this once obscure little market town, tucked away on an old Ottoman trade route between central Anatolia and the Black Sea, has acquired emblematic status for architects, social historians, town planners and conservationists.

Originally a Hittite settlement 4,000 years ago, its greatest prosperity and current shape date from the Ottoman 17th century and the development of the Gerede-Black Sea trade route. Blessed with raw materials, such as the valuable saffron from which the town derives its name, a comfortable setting, rich surrounding agriculture and forestry, Safranbolu developed into a trading and manufacturing centre in its own right.

The town boasts a glorious collection of old Ottoman houses, so beautifully preserved that it qualifies as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In Ottoman times, prosperous residents of Safranbolu maintained two households. In winter they occupied their town houses in Çarşı situated at the meeting point of three valleys and protected from the winter winds. During the warm months they moved to summer houses amid the vineyards of Bağlar. No house blocks the view from another. Some of the largest houses had indoor pools, which, although big enough to swim in, were not used as such. The running water cooled the room and gave a pleasant background sound. Several historic houses have been restored and, as time goes on, more and more are being saved from deterioration.

Again we arrived in town before nightfall in time for a visit to a vantage point where we could view the town.

Day four

We spent the following morning strolling around the town visiting the handicraft shops and stocking up on supplies of saffron. Safranbolu is the only place in Turkey where it grows.

After lunch we set off for Ankara airport to complete a fascinating and memorable tour.

Text: Christine Davies with the help of our guide, Suat Dingil, the Lonely Planet Guide and Cornucopia issues 19 and 47

Photos: Netia Piercy